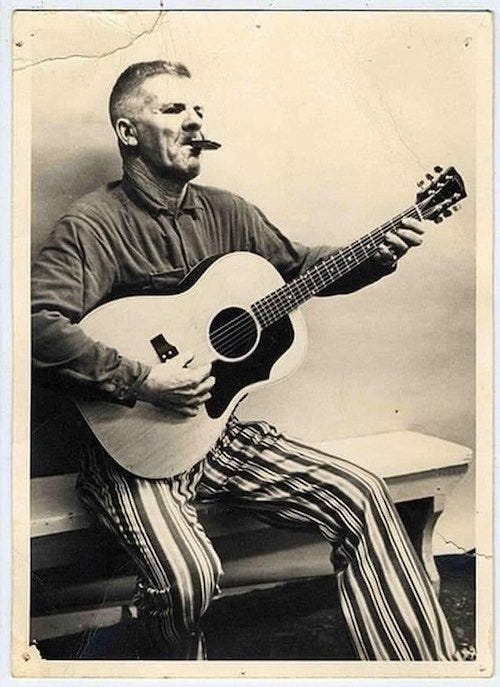

Before There Was Elvis And Before There Was Dylan There Was Harmonica Frank: The White Outsider

Why is Harmonica Frank such a major figure and why am I writing about him and posting it on Substack? And why have you never heard of him?

Well, he was an obscure, Southern white guitarist/singer who lived his life (he died in 1984) on the kind of musical stages that pretty much don’t exist any more: tent shows, medicine shows, minstrel shows. He also, luckily for us, in his prime years, recorded for Sun, which issued the attached performance, She Done Moved, as a 45 (recorded in 1951 or 1952). His reputation was rehabilitated (somewhat) by the great Greil Marcus, who wrote a chapter about Harmonica Frank in his book Mystery Train.

Before I read that chapter I had no idea who Harmonica Frank was. But one read and a few listens later I was just floored by his infectious and socially off-key performances, put across with a persona that seemed to reject the shallow way in which so many musicians try to ingratiate themselves with audience, in favor of what sounds like just plain raw entertainment of the most happily, casually subversive kind. Because I quickly realized that here was a performer who encompassed an entire history of a little-recognized, pasted-together art form, as a kind of hybrid, pop/folk/blues/white/black/songster/medicine show/minstrelsy stylist, a singer without portfolio – actually. a performer without style, which was, indeed, exactly his style. As a matter of fact Harmonica Frank may be the ONLY performer in this somewhat obscure category; there is just too much there to consign him to any one corner of the American vernacular.

But that’s the point. He represents (and he recorded into the 1970s) what sounds like a summation of, well, not everything that came before him, but really an accumulation of an almost bizarre amount of American musical baggage, of the right (for a singer), utilitarian kind. In a way, it is not a surprise that this was all the work of a white singer, especially a Southern white singer. In a cultural way he, like all whites down South who tried to sing in the wake of that mad mix of black song as it all thrived in the shadow of Jim Crow, was a true outsider. He knew the blues, though he sang it with a masked sarcasm and strange mimicry that was, essentially (whether he thought of it that way or not) a commentary on the blues and the fact that a journeyman white singer, an outcast and a observer who was not afraid to jump right into the middle of it all, could turn life into – well, let’s not call it art, though that is exactly what it was. He turned it all into material, into an act, and gave us a true example of early (if unrecognized) Performance Art; and it was truer than most Performance Art that I have experienced because it was absent any taint of artistic self consciousness, which may be THE (or really another partial) definition of Art, especially valuable for its escape from the contextualized corruption of academia.

Listen at 1:05 here for one of several astounding revelations in this performance, as he sings “gotta move baby” with, amazingly, the guttural inflection that Elvis turned into a signature. That particular gesture is all over this performance, as is a sense of distance and self-amusement at what Harmonica Frank himself is making of this strange pop/serious form, The Blues. It is the blues, coupled with the musical alienation effect of minstrelsy, (a “discredited” form that has everything to do with American music whether we like it or not).

Who does that bring to mind? Another quintessential White outsider, yes, Bob Dylan, whose recordings ten years later show a nearly identical conceptual brilliance, as another of the few white folk and blues singers who understood that the original blues men and women, if in a much different way, kept their distance from the “meaning” of the song, as though they understood that as soon as something became consciously meaningful it lost all meaning. Meaning (pardon me), that they had the classic literary understanding of how artistic detachment (not the same thing as irony, though they often intersect) could serve as an antidote to the smothering ego and the curse of self-obsession. Take a step back, they tell us, and you will hear and comprehend more than if you are standing eye-ball to eye-ball with a song (or a novel, or an essay). This, indeed, is a lesson lost in much of American music today, from pop to jazz (but that’s another essay that will annoy, I am certain, some jazz musicians).

So it goes with the classic White, musical outsider, and Harmonica Frank’s prophetic view of a musical world to come, in which Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan revolutionized the pop aesthetic, if only for a brief time – though it was long enough to change American music in irreversible ways. Because this trio of musical figures – Harmonica Frank, Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan – all started life in worlds that did not at first know what to make of them, though Presley and Dylan broke though quickly by tapping into a specific aesthetic and personal need of white folks, in particular (though Elvis had a huge black audience). The result was to turn one kind of racial alienation into a form of action that was, yes, popular art.

Were they the first white people to do this? I haven’t thought about this long enough to give a real answer to that, but the truth is that even today white jazz artists (in particular) all fight social preconceptions of the kind that did effect Elvis and even Dylan at different times, about authenticity and acceptance on certain social levels. It can have a deleterious effect on life and career, especially if, as a white musician, you encroach on stylistic areas that are seen as the domain of African American culture. And even if that is not the ultimate problem (racism and economic inequality are more decisive in exacerbating the increasing division of Aesthetic America), categories matter (no matter what anyone tells you).

Most people will tell you that if you are white you are intrinsically an insider, and though this is true in many ways, there are different levels, different kinds of alienation. Ask any therapist. Life is never easy for those who see and hear things from a different perspective (which is what made this trio of performers so great), and death, anyway, is the great equalizer.

As Lester Young said “Until death do we part, and then you got it made.”

This knocked me out: "But one read and a few listens later I was just floored by his infectious and socially off-key performances, put across with a persona that seemed to reject the shallow way in which so many musicians try to ingratiate themselves with audience, in favor of what sounds like just plain raw entertainment of the most happily, casually subversive kind."

And this bears repeating until it's memorized: "Meaning (pardon me), that they had the classic literary understanding of how artistic detachment (not the same thing as irony, though they often intersect) could serve as an antidote to the smothering ego and the curse of self-obsession."

I read Greil Marcus, so I actually „knew“ more about him before I heard him. When I finally got the Chance to hear his Stuff in „My Record Store of Choice“ I didn’t buy it. Reading about him sounded better in my Brain than actually hearing his Music.

I got more out of Cajun, Zideco and Tex Mex of the 30ties.

Hokum and Jug Band Music and the String Band Stuff as well as Guitar Rag (aka Country Rock) of Blind Blake rocked me more.

But now I will give him another Try.

Between reading Greil Marcus and hearing him about 3 to 4 Years passed by, that might have screwed up my Expectations to high.

There is a (Hand) Harmonica Guy from Muotatal in Schwyz, Switzerland I was listening to back then who rocked me more (I am quite weak when it comes to European Music, but that Guy was the only one who could keep up with the Tex Mex Guys).

I can listen to Minstrelsy Music as I can listen to Merle Haggard or Chic Corea or Ike Turner. If it is great or significant Art I want to know about it.