COLOR ME WHITE: The confusions of race or, WHAT DID YOU CALL ME? How delusions of racial purity have taken a reverse course in American Culture

I am on the verge of an epiphany. Or a nervous breakdown. I will let you decide.

Actually it’s in regard to something I have been aware of for years and have talked about, cautiously, on social media. In the past when I got into public arguments with public figures like Nicholas Payton and Rhiannon Giddens on this general subject there has been some backlash – or maybe I should call it a back splash, as the ripples from the responses of some people have come back to douse me with different degrees of hostility.

It is simply this: Black music is white and white music is black and we do best to examine black culture by looking at the larger, and stranger, racial picture ecunemically. After dealing with this idea of culture and sound and rhythm and language for so many years I have come, with some finality, to that conclusion, and I have no hesitation declaring it as a discovered, empirical truth. It doesn’t mean we live and breathe and work on a level racial playing field. It doesn’t mean the Smithsonian should continue taking down all references to African Americans and African American equity, or that we should run as fast as we can from DEI; or pretend that we are living in a post-racial world. Tell that to George Floyd – wait, no, you can’t, because he was murdered.

But, also, yell it on the mountain, because what would James Baldwin say? Would he agree with Harmony Holiday that white blues is all thievery? Or would he engage in an internal debate about the role of ideology in determining truth? And, when it comes to race and the deepest expression of feeling and, finally, music, does my whiteness – does ALL whiteness – put a stopper to the emotions that we all feel are bottled up inside of us? Or, at the end of the day, as Alberta Hunter said, is it “all the same in the dark”? Does racial consciousness counter racial self-consciousness and so put us all in a different space, on ground that may not be level but which is continually shifting beneath our feet, setting up new and more complicated power relationships? Can I, a white male born into the middle class and raised in a land of white people, take a stand for the kind of sound I want to make, even when it is not derivative of any strictly white category of culture?

Well, maybe I can because I have finally come of age enough so that I can stand back and stop worrying about what anyone thinks about what I believe. Though I have to say I felt this way thirty years ago; but maybe now it’s a little bit safer to go public - or maybe, in the age of Trump, with all of our racial nerve endings fully exposed, it’s less safe. I don’t know, but after five years and 22 surgeries and a regular feeling of imminent death, after waking up day after day to the dread of having to make it through another one, maybe nothing can really touch me in a way I have not already been touched. Or hurt.

But here is what I think: America is essentially a black country in which white people, some against their will and most against their knowledge, are essentially black. Sure, whites maintain their own personal essences, they are often socially apart, they pray in different ways; but when they walk out of the house they enter a country where the sun never sets on certain ways of blackness, on the active use and acceptance (and purchase of representations) of black language, movement, sound, and rhythm.

It wasn’t necessarily like this 100 years ago. But as the folk sources of American music recede into the distance, as the stigma of minstrelsy fades into a memory corrupted by false assumptions that it, minstrelsy, is/was simply an evil white fantasy; when in fact it was the medium that, ultimately, allowed black performers and blackness itself to establish a cultural beachhead in the USA; the distinctions between black and white become harder, in certain respects, to make. There is appearance, color; but at the end of the day those are the shallowest and least important distinctions. What matters, what makes white people as real as black people, are the ways in which cultural strangeness becomes cultural habit.

Michael Bloomfield played the blues, begging at first for black approval but finally, in his rapid maturation, staking his own claim for a sound that was – well, as American as apple pie (to quote H.Rap Brown in another context). Dave Schildkraut, a saxophonist born in Brooklyn into a white Jewish family, became the equal of what clearly were his black peers. He was not culturally deficient and he was not racially deficient. His black peers recognized this and, in the heat of the musical moment, recognized his greatness. For that brief moment that world was color blind; that immediate moment was, truly, post-racial, because it transcended assumptions and prejudices as everyone just focused on the feelings Dave emitted, on the reality of Dave Schildkraut playing “with so much soul” (as Art Pepper said to me years ago) that even Charlie Parker admired his playing.

Anecdote time:

I am working in a band and one day a member of the band (who is black) tells me I play like a “Ni****.” I don’t know if I should thank him or deny it (out of modesty or a sense of propriety), but I just smile and move on. It is undoubtedly a high compliment. But he is just responding in the moment, as good jazz musicians do.

I put out a CD project of all blues and old black musical forms, and one estimable critic calls it “a landmark.” And though I am proud of that accomplishment, I know that when I make certain cultural claims they are fraught with guilt-by-racial-association. So instead of making a big deal of it I immerse myself, over a thirty year period, in the deepest aspects of black music, of sounds that defy stereotypes, of black songsters singing ragtime and minstrel and pop tunes, with nary a blues phrase in them. Are they less black than they would be if their voices didn’t carry with them the curse of minstrel inflection, the curse of that old phrasing as it embraces words like “coon,” all in a real and authentically black voice?

Are they any less black because nobody knows them any more, because no one hears their songs, because those songs themselves seem contaminated by elements of disreputably black-by-association culture, of the kind that appears to just be old-time, plantation, “massa” this and “massa” that subjugation? Or are they true pioneers because they stood up and asserted their individuality and their right to – well, their right to stand up, in a world that was dangerous and constantly threatening them with one form or another of violence? Is it, indeed, easier for a white boy like me to accept them because I have embraced, at least unconsciously, the old idea of social distancing, which has allowed whites to observe black people and black culture from a safe physical and social distance?

Probably. But that does not make me wrong, nor does it make me delusional. As a matter of fact it means I have refused to submit my cultural opinions to anyone for pre-approval. And that is a good thing.

And I play and write, therefore I am. I refuse to bow to false racialist posturing, like with the African American critic Jordannah Elizabeth, who has written the following, in language that I find highly insulting on many levels, based as it is on a a lack of exposure to a vast and brilliant literature, by white critics, on aspects of African American music and life; she tells us:

"White writers don’t have the emotional, experiential, existential, historical connection to jazz. I got my experience through following bands, listening to my elders, and really reading and studying on my own.”

Does anyone remember the genius John Szwed, one of the founders of the modern concept of Africana studies, a white guy who has done some of the most important work on the Diaspora and American culture? Or Archie Green or Roger Abrahams, or Max Harrison, or Larry Kart or Tony Russell? All white critics whose work is central to our understanding of American music and American culture in all of its aspects? Or the academic literature on Africa written, yes, in the days before black academics were allowed into the club, but which was done, at first, with faith and brilliance, by white academics like Melville Herskovits (who, as PBS has said “was the first prominent white intellectual to declare that black culture in America was ‘not pathological,’ but rather inherently African, and that it had to be viewed within that context”)? Or the white field collectors like Howard Odum and Dorothy Scarborough who, for all their foibles, were out there collecting the work of black oral poet/musicians when few were doing same? Should they be cancelled because Jordannah Elizabeth has questioned their abilities to understand the subject?

No - they should not, and we SHOULD promote the work of black scholars as they offer new signs of resistance to the hegemony of white academia - but not at the expense of those white men and women who stood up to that hegemony in the early days, and who finally allowed some light to be shone into the unexamined corners of American - and most particularly black - life.

But Jordannah Elizabeth has not spent 50 years, as I have, studying the music and its history, paying dues by refusing to compromise on critical and aesthetic standards and by teaching myself the forms and ideas and language of African American music; and then by teaching others how those forms and ideas and languages evolved and developed in aesthetic and historical ways. I have earned my way in, not inherited it like a Legacy student at an elite university.

And there is Farah Jasmine Griffin, an African American academic who wrote a biography of Billie Holiday which described a recorded musical encounter Holiday had with the white pianist Jimmy Rowles as though Holiday regarded him as a necessary evil, an ofay pianist she was forced by circumstance to work with, but one with whom she intentionally kept her distance.

Nonsense – Holiday loved Rowles, and there is literally no evidence to indicate that she regarded him with anything other than respect, both artistic and personal. This is something of a reverse image of white writer Sherry Tucker’s claim that Holiday was ashamed of her blackness; Tucker tried to illustrate this by discussing how Holiday first recorded on the West Coast with the Paul Whiteman band and then later, rejecting a black, women’s big band, wondered why they could not accompany her like Whiteman’s did. Tucker, who had no idea that Holiday was making a musical judgement and an aesthetic statement, saw this as racial self-hate. Billie did not like the women’s band, thought they were too loud and intrusive. But Tucker’s willful misinterpretation of this was totally ideologically based, and she used it to confirm the false assumptions that she, as a white academic totally divorced from the professional reality of jazz, had.

And so we precede, on the media side, with fake reparations. What disturbs me about so much of the arts’ world’s attempts at outreach to people of color is that it tends, in itself, to be applied in a racist manner; the white folks of the middle class persuasion who occupy so many arts groups, lacking as they do any real understanding of American/black culture, see only color, and in the process they go for image and shallow social posturing, in the process leaving out many great black writers and musicians and, I assume, black artists in other disciplines. This exclusion leaves the granting process to fawn over the same few musicians, some of them already successful, at the expense of the deeper musical population of African American talent (like, for example, and just for starters, Dom Flemons and Matthew Shipp); that population doesn’t posture and spend its time subjecting itself to another, yet quite ironic, kind of subjugation, which calls for certain artists of color to tailor their art to a system of grants and other money that rewards socially obvious themes, that prefers esthetic glitter over the kind of deep devotion to personal art that actually lasts beyond grant deadlines.

Of course, it is not only white administrators who do this; the virus of false artistic racial consciousness has infected even people of color who run organizations, who make it clear that they have no use for white folks of any kind. Some might see this as a justified flipping of the social script – and it certainly is, in some respect. But the novelty has worn off. Now we need some honesty and a sense of complete, not just selective, fairness, but I don’t think we will get it any time soon. Where I live I have been almost completely shut out of a world arts festival that will not even respond to my queries, and which persists in promoting mediocre work that qualifies only by virtue of its supposed woke-ness.

I believe there was a study some years ago which concluded that imagination was as useful a tool in learning and absorbing culture as experience was. I find this fascinating, and I think it explains a lot. It explains Dave Schildkraut, Al Haig, Jimmy Ford, Terry Gibbs, George Wallington, Stan Levey, Ken Peplowski, Pee Wee Russell, Boyce Brown, Bix Beiderbecke, Loren Schoenberg, Aaron Johnson and countless other white musicians who have given their lives to jazz and have done so with brilliance and integrity. And it is not that they did not study music or that they got it all by some mysterious and unnameable type of osmosis; they studied and apprenticed, as black musicians studied and apprenticed. But they all came from outside the culture that ORIGINALLY created and nourished jazz – and they were able to surmount this “obstacle” because by the time they came of age they and other white folks were no longer truly cultural outsiders. Once that cultural genie was out of the bottle there was no containing it with racial covenants that covered their tracks with claims of “authenticity.” As Ralph Ellison pointed out, culture is not passed on genetically but socially, and jazz (and other forms of black music) was there for the taking.

Once again, I backtrack slightly by refusing to downplay American racism and the need, on so many levels, for social reparations in this country. But truth is truth, and sound is sound. It’s just that I crave a TRUE type of diversity, where race is measured against quality of work and where artists forge a community of equity and respect.

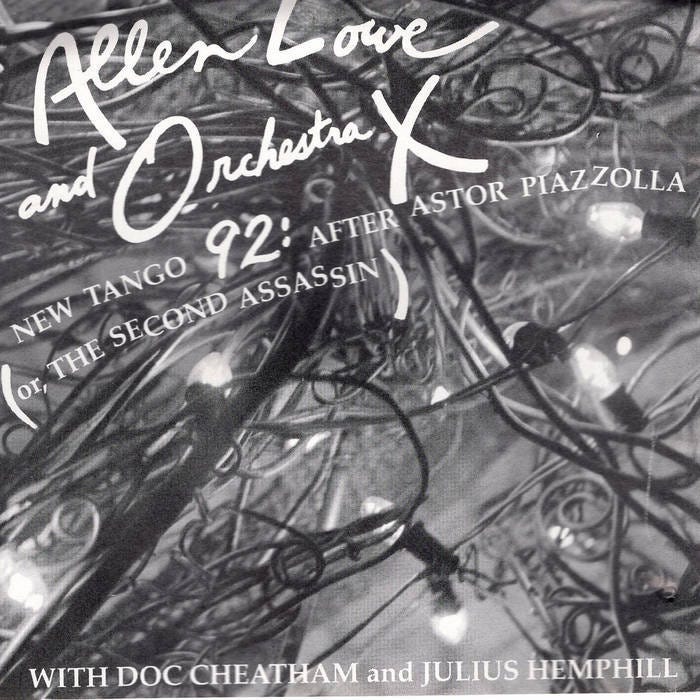

And I will close with a one of my own experiences; after, a few years back, I wrote on Facebook about my working and recording with the saxophonist and composer Julius Hemphill, a black musician posted about how it was typical of white musicians to try and latch onto black musicians to advance their careers. I don’t know if this was more insulting to me or to Julius; it was basically saying that he was too dumb to realize that he was being used by a white guy, as though Julius was a passive receptacle of exploitational racism. And that he was letting himself be used by me, a lowly white musician, in order that I might crassly advance my “career.”

But I knew Julius. I liked Julius and he liked me. We recorded together twice, and would have done more if he had not gotten sick (he had to cancel a third date). There is a compact disc of a night he performed with my group at the Knitting Factory, and I am very proud of it. He liked my compositions, he liked my playing; I know this because he told me so, and Julius was not a liar or a sellout, someone who freely handed out compliments. He was simply a great musician who was showing some respect for someone who, like himself, loved the music and was trying to play and compose it with honesty and dedication.

I don’t really know how to end this except to strongly suggest that you look at the world we have created and how it is being debased by narrow and exclusive social definitions, of the kind that tell even old, tired, and occasionally sick white musicians like myself that we need to learn our place and then stay there. But I won’t go gently; I never have and I never will.

The retroactive history we've seen promulgated for decades is contradicted by the long history of amity and respect between black, latin, island and white jazz musicians. To blow my own horn (and I play trumpet), I go into this in detail in "As Long As They Can Blow: Interracial Jazz Recording and Other Jive Before 1935."

An interesting piece that I would say gets 2/3 of the way there, because there is a far too often unacknowledged third category (caste?) in American art and culture. Things are not just black and white; they are black, white and *brown*. Latin people and their contributions are ignored *all the time* when American culture, especially music, is discussed. For starters, is Latin jazz jazz, or is it some other thing? Given Eddie Palmieri's oft-expressed love for McCoy Tyner, to pick just one example, there's a discussion to be had about other forms of inclusion and exclusion.

I would also add that there's a particular (not-so) new twist on this "you can't do that" discussion happening in the 21st century. For the last 40 years, the dominant form of American popular music has been hip-hop, and hip-hop has influenced every other form of American popular music, including jazz. (I have had some very interesting discussions with younger and older jazz players about how young drummers hear rhythm differently, because they grew up with the looped beats of hip-hop rather than the constant fluctuations of swing.) But some critics, I think particularly of Ann Powers at NPR though she's far from the only one, continue to condemn white pop performers like Miley Cyrus for incorporating elements of hip-hop into their work, as though this is some sort of thievery, rather than proof that culture is a buffet open to everyone. If you're under 40, hip-hop is the air you breathe, the water you swim in. It would be stranger for a young musician to choose *not* to engage with hip-hop.