Mezz Mezzrow and The Fog Of Tenure: Racial Profiling by Critics and Academia: (Or: White Like Me: For A Change Let's Listen to the Actual Music)

Sometimes people wonder why I have such an “attitude” towards academia and the academics who occupy it. Well, how much time do you have? I will give you the (semi) short version: the biggest problem I see with academic approaches to American music writing is their tendency to take a small (ridiculously small) sampling of various genres of music and then generalize about that music in books that are over-written and clogged with opaque language and contextualized but empty “meaning.” Though there are some happy exceptions, I have seen this over and over again. As a matter of fact, I don’t remember the last “academic” book on American music that I read that was, in the historical evaluation of primary musical sources, accurate or thorough (Lewis Porter’s John Coltrane biography comes to mind as a perfect example of the right approach). As a matter of fact, when it comes to certain musicians this shallow methodology amounts to Cultural Racial Profiling. So I give you, for your consideration: Mezz Mezzrow.

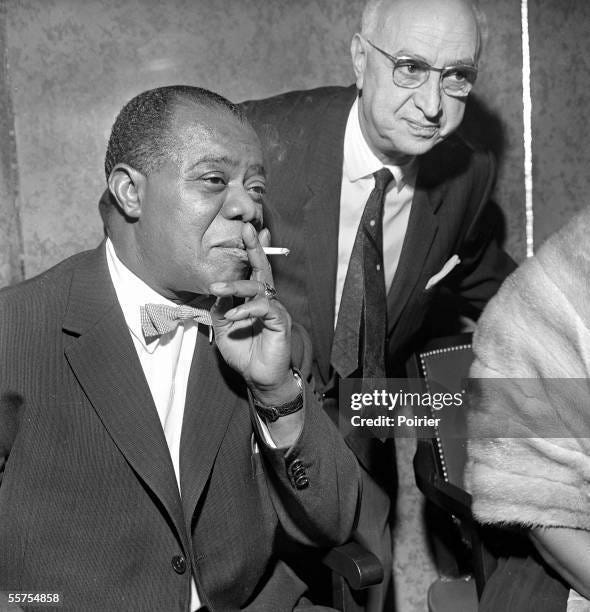

Mezz Mezzrow: Sendin’ The Vipers

Mezz was a white Jewish guy from Chicago, primarily a clarinetist, with some dogmatic (well, maybe just persistent) ideas about race and music; someone has called him “a voluntary negro” and for once this was an accurate depiction of a complicated and very interesting historical figure. He wrote a book, an autobiography which I love, called Really the Blues. Though he is often criticized for his postures of sometimes exaggerated Negritude (an old phrase that I use cautiously for fear of being misunderstood; but at one point it was used to indicate certain proto-Black Nationalist ways of emphasizing blackness), in this he was, strangely enough, au courant. His book should be read rather than read about, because no one on the academic side who writes about it seems to sense how historically interesting and significant it – and he - is. Mezz was witness to those early years of jazz when the music struggled to get to its aesthetic feet, to navigate the bridge between white and black America without sacrificing its own racial identity or losing sight of its own artistic and technical needs. All was complicated (or really fragmented and distorted) by racism, but a few essential white folks charged through the apparently impenetrable barrier of race to establish a presence of either musical accomplishment or commercial/critical support – or both. Mezzrow was the the latter; even if some of his racial aspirations might, to us, seem dated (and they probably are) he more than meant well, he put his beliefs into action by organizing integrated bands to record, by being a tireless advocate of Black Music (not a common thing for white folks in those days), and, most importantly (because without this I would not be writing about him) by being a good musician who was also a great bandleader. His small group recordings from 1928-1936 in particular are models of tight musical organization and wonderfully expressive group interplay, of beautifully integrated solo work. Very much of their time, I love them because they are very much of their time. And did I mention some of his great, futuristic titles, like Revolutionary Blues and Free Love?

(And I should mention that he was a pioneer of Cannabis advocacy, for which I am doubly grateful; were it not for people like him I would likely be in an institution somewhere with restraints applied, suffering from post-traumatic-sleep deprivation, nervous exhaustion and psychosomatic despondency; such was my condition a few years back when, post-removal of a large part of my nose, I went six months virtually without sleep - and virtual sleep was about the only sleep I got - and was only saved by the discovery that a THC gummy or two before bed could be a balm and psycho-physical savior, and ensure actual sleep. So thank you, Mezz. You were far ahead of your time.)

Maybe it helps, from my point of view, that Mezztow was white, Jewish, and had absolute integrity in his approach to jazz and jazz performance and racial matters. I was praised once by Anthony Braxton for not being a self-hating white man, and I accept that honor by noting that I have spent more than half my life writing about, explaining, and advocating for African American music without exploiting or profiteering (though lord knows I have tried). I have little to apologize for (though I accept at least partial responsibility for the continuing sins of White America) and, like Mezz, I forge on even in the face of certain kinds of critical indifference.

But to get back to the academics – ALL THEY DO is write about what they think is Mezzrow’s conflicted and contradictory life of racial (mis)identification and supposed personal embellishment – but first of all, let us remember, he was NOT conflicted but steadfast in his ideas and musical ambitions and in his real sense of racial justice. He was a Civil Rights Pioneer, plain and simple. And second of all, and this is most important, those academics who flail away at Mezzrow’s supposed racial failings – we are in Mailer ‘white negro’ territory here – have for the most part NEVER ACTUALLY LISTENED TO THE EFFIN’ MUSIC THAT HE MADE. And if they did it was usually just to illustrate some arcane sociological idea or as a means to leverage some sort of irrelevant academic theory or hypothesis. And as I indicated above, Mezzrow was a solid musician and a great bandleader who put together wonderful, integrated, bands who made great and significant music.

Listen to the musical performances I am posting here; the sound of it all may be foreign to contemporary ears, but be aware of the pervasive and unforced blackness of the performance style, by white and black musician alike. In the earliest years of jazz, white musicians were still becoming acclimated to the sound and rhythm of all this new, essentially black, music; but by the 1930s the distinguishing stylistic factors, between white and black, were starting, in more than a few significant cases, to dissolve into a common dedication to just making music, to acquiring a feeling for the common tradition of American song: for the blues, for pre-blues black expression (like gospel and spirituals), and the spoken language of black life; and for minstrel remnants of song and instrumental gesture, and the overall feeling of jazz as a new and growing language. Yes, for those of you out there who get their dander up at the suggestion of any white/black equivalency in the making of jazz, racism was pervasive and White Supremacy was a sword that hung over the necks of all black people in America. But as Richard Gilman has said (in a literary context) these Americans, black and white, were forging an alternative history, a counter-narrative to the tawdry realities of White America.

And we do have the music, if only we take the time to really listen. Which is why I am here, today, writing about Mezz Mezzrow. As you listen to this, realize that solo expression was a much different thing for most jazz musicians in that day, that the secret to the greatness of these recordings was rhythm and phrasing, musical purpose and a commitment to a way of punctuating phrases and manipulating the time in a swinging way, a fluid sense of both forward and backward musical/rhythmic motion. Momentum in these recordings was not simply a matter of rhythmic propulsion but of time and tonal implication; improvisation was less a matter of harmonic invention than it was of feeling and subtle displacement of tempo and phrase.

swinging af. i only knew about the club in nyc called after him but nothing about either his story or music. thanks for sharing!

Nice to see this. I came to learn about Mezz through knowing Sammy Price and their great recordings together. I found Mezzrow’s Really the Blues to be an exceptionally well written and enjoyable autobiography, one of the best.