This is a long one. In Part 3, next week, I will give a bunch more musical examples. This week I give a windy explanation with three fascinating musical examples. Take what you can get.

SO where did jazz begin? If not New Orleans, where? Where? Where?

This is one of those questions that will be asked for as long as anybody really cares. I do; why? Because the complexity of the music matches the complexity of its origins, and there is so much strange disinformation that floats around the jazz world like a heavy cloud of both shame and joy (we love the music but are troubled by the label jazz; in that case, re-read my last column on jazz origins and the etymology of the term).

So; do we dare talk about early white jazz performers like the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, the Louisiana Five, Earl Fuller? Of course we do. This is not a revisionist history. We are not claiming that the pale-faced, post-ragtime orientation of some of the early recording artists proves that white people did this before anyone else. They did not, but we just have to be aware of the fact that since black musicians were largely (though not completely) excluded from American recording studios prior to 1920, our ability to look at the timeline of what sounded like and became early jazz is somewhat stunted.

What we have to do (as with other forms of American vernacular music) is listen to all we can listen to from the pre- and early history of jazz performance, in order to get a sense of the sounds that were mingling together in those early years, as jazz struggled to assert itself as a style and method. Not to mention the racial mix that finally emerged most prolifically after 1923, as American record companies finally woke up and realized that the fear of race mixing was less important than the fear that they might miss the opportunity to make a lot of money.

It was the historian Dick Spottswood who alerted me to the fact that, early on, domestic record companies, though largely ignoring black American performers in the first part of the 20th century, WERE recording people of color from such hot spots of the Diaspora as Cuba, Martinique, and Venezuela. I spent a fair amount of time, years ago, checking out historical recordings from those places, and I came to one basic conclusion: though the clave rhythm may be seen as the basic entity of jazz’s newly subdivided idea of swing (see part one and my discussion of what I call the African Triplet), not all manifestations of the clave are equal or the same.

What I concluded (and which I wrote about in volume one of my two-volume book series on American music, Turn Me Loose, White Man) was that the Caribbean rhythms of Cuba and Haiti, for two examples, while distant relatives of the jazz impulse, were too clipped and brittle to represent the new, American, idea of Swing. Though this new concept of swing was clearly related (especially in the occasional eruption of the so-called – and I hate the term- Spanish tinge), the U.S. version had its own peculiar and distinctive flow. Listen to the recordings made by the Venezuelan pianist Lionel Belasco. Though they are not jazz in any conventional sense, they have a free-floating way of accent and a gentler sense of rhythmic motion which is much closer to American jazz’s idea of momentum and swing (an example to follow).

So, to make a really long story short, how do I believe that jazz developed as a means of rhythmic variation and, finally, black swing and improvisation?

Well, where to begin? First I want to quote a friend of mine, Rob Chalfen, a brilliant music historian with whom I actually disagree on the question of New Orleans; but Rob has written:

“My Theory is that there were a large number of musical ingredients that comprised African-American music especially band music in North America c. 1910, but that New Orleans is the only place that pretty much had all of them percolating in a gumbo that reached critical jazz mass - you can hear via various early recordings from other locations that there are some elements present but not others - it's a spectrum - Sweatman from Minneapolis has ragtime, march, minstrelsy, a bit of blues, not much actual improvisation - the Martinique beguine bands have improvisation, raggy syncopation, the French thing, but no march or blues. The early Cuban bands (Pablo Valenzuela 1905) have African rhythm, Spanish clave, polyphony, march (brass band) thing, but no blues or Francais. The New York style by 1920 (Bradford bands) have blues, some improv, polyphony, rag, minstrel, but no French or Spanish tinge. The early SF bands (Hickman 1919) have a loose polyphony, rags, but no real blues, Creole or much Spanish tinge. Handy's Memphis band 1917 has rag, blues, march, some chaotic polyphonics but no improvisation to speak of, no French Creole. Only the New Orleans bands show all the critical elements out of the gate, which is why that's the style that electrified the country - sure it incorporated all sorts of things on the way but the New Orleans. cats had the killer app.”

I don’t disagree with Rob’s dissection of the elements – but I do think he is incorrect in coming to the conclusion that, because of the convergence of certain key musical ingredients in New Orleans, that that was where jazz began. Maybe that is where it reached, in the early days, its highest point of development, but I think it’s a mistake to assume, because of blues and certain rhythmic innovations, that this is an accurate origin theory. I do agree that his listing of essential musical elements is sharp and to the point, but I tend to think that these elements, as they converged, were effect rather than cause. Meaning: jazz was the result of so many disparate elements that there may be a reason to look at New Orleans as the end result of a musical Big Bang. That, however, ignores too many other sources and trends along the way and, in particular, it misses an important reality: American record companies, in the crucial early years of the twentieth century in particular, failed to give us a solid and comprehensive documentation of black American musical habits. So we are left to make presumptions, to guess, and in doing so we (well, I) reach certain conclusions.

As I have indicated in my prior column on this subject, improvisation is not essential to jazz but rather an aspect of jazz form that took time to develop. Early jazzers were likely to have used phrasing and rhythmic variation as a means of pre-jazz invention before moving to the next step, which was to restructure melody as contained and related to the accompanying harmony (and though those earlier kinds of variations might be argued to be acts of improvisation, I would argue that they are acts of variation and paraphrase, which are not the same thing). So, we get early jazz groups like San Francisco’s Early Fuller, the Louisiana Five, The Original Dixieland Jazz Band (yes, from New Orleans), James Reese Europe (see part 1) and, most significantly, the early Eubie Blake recording of Charleston Rag (1921). Charleston Rag, from a black pianist who was based in Baltimore, is an astonishing work that is neither ragtime nor stride, but a brilliant fusion of both, in a way that EXACTLY predicts the jazz musical impulse. And, I repeat, it is not from New Orleans.

We should note that a key to the spread of all of this new sound was the Northern and Western migration of not just New Orleans players but of SOUTHERN musicians in general, like trumpeter Bubber Miley and trombonists Jimmy Harrison and Jack Teagarden, who brought a fitful blues orientation to their music, but also a way of playing that was revolutionary and revelatory to many other players. Plus we need to be aware of the springing of aesthetic leaks of newly improvised music in certain regional hot spots; Teddy Weatherford (pianist) in Chicago, Earl Hines in Pittsburgh (initially with the singer Louis Deppe), for two. And finally, yes, Louis Armstrong burst through like a nuclear bomb, and yes, he was from New Orleans, but, once again, to me that does not prove New Orleans was the epicenter, only that it was very advanced in its musical outlook – but also, given the lack of recorded musical documentation, who knows what deeper things were going on regionally? Remember Jabbo Smith, the trumpeter from Georgia who was not only, in my quiet opinion, the equal of Louis Armstrong but who would probably have, if he had stayed the course, surpassed all of the pre-swing and swing trumpeters, including Roy Eldridge? All of which is why I am so cautious about making certain assumptions and set-in-stone pronouncements.

I also think that it wasn’t THE BLUES which was the final and decisive ingredient in the blackening of American sound and the creation of jazz, but rather the pervasive influence of the growing black Sanctified Church movement and the historically complex performance practices of black musicians and other performers from all around the country – not all of whom were blues oriented. Take two early black musical pioneers: Earl Hines (piano) and Coleman Hawkins (tenor saxophone). Neither of these two were particularly good, in the early years, at playing “the blues.” They had a completely different aesthetic orientation and musical mindset, and it is significant, for example, that in Hawkins case he was so heavily influenced by Casal’s early recordings of Bach. Casal’s phrasing and sonority clearly had a major impact on Hawkins, and they were not blues; however Hawkins’ own sound and phrasing and means of rhythmic variation were clearly from an African American tradition that had other ways of implying soul and spiritual depth. Here is Casals; I can almost hear Coleman Hawkins breathing one of his epic tenor solos; and Hawk’s tenor sound is really very close to this:

Whether these black interpretations were from an oral tradition or the church, or, in this case, a phonograph, we cannot say for sure. But we know, as well, that Hines was not an effective “blues” player. He was a genius pianist, clearly “black” in the way his dotted, slalom-like rhythms re-mapped the whole idea of standard song; but it was NOT the blues, it was a deeper and more complex thing that came from the sing-song rhythms, I would say, of black speech and the stepping amusements of black dance. As for Hawkins, his blues playing did not bloom, I would say, until the 1950s. He had to learn how to play the form effectively, which tells us something about the assumptions we tend to make about race and expression.

As Ralph Ellison reminded us, these things were not genetically transmitted but rather passed on through the culture. And black culture was not only a complex thing as also bifurcated by class, but it was also heterogeneously united; the elements of that culture were related and had sometimes mysterious and even un-documentable interconnections. The cumulative effect of it all amounted to a kind of cultural call-and response, even when specific black artistic disciplines had very varied attitudes and outlooks. But it did not matter; Coleman Hawkins was a genius of improvisation and implied, in all of his comprehensive ways of playing the harmony, a world of black sound. It is just a different world, perhaps, than that with which we are (somewhat) familiar.

How do I/we assume all of this? How do I/we make these connections? There are just so many (too many?) sources that must be consulted in order for us to get a true sense of black music as it functioned before and just-before jazz, sources that we need to comprehend before we try to understand the pre-jazz implications of black performance.

The writer Lafacadio Hearn has given us some astonishingly clear and detailed descriptions of the black cultural underground in Cincinnati where he lived in the late 1800s (Hearn, born in Greece, was a white man who was living, in that period, with a black woman, and he was clearly dedicated to documenting the culture of the black roustabouts who worked the port of Cincinnati). This wasn’t jazz but it was a regional eruption of black sound prompted by not just the presence of so many African Americans but by the cultural isolation of people who had to make their own entertainment, and who did so largely (but not totally) out of the view of white folks. But as Hearn tells us, it was full of expressive unorthodoxy, deep, pre-blues, emotional variation, a credible and deeply artistic mix of the personal and the communal – meaning that the social isolation of black people was an inadvertent form of liberation, freeing them to talk and sing and dance their way out of the deep psychological holes that White power had dug for them, in ways that were personal (autobiographical, the pieces of their lives) and communal (intended to communicate common feelings to an audience of their peers).

And this process, reflecting as it does a deeply artistic means of articulating, in real time, the frictional clash of the private and the public persona, is a brilliantly prescient prediction of the coming tropes of the new modernism of even European literature, not to mention a sign of the intellectual process that led to radical aesthetic developments in the new European and American “classical” music of the coming decades (and in dance and in theater). Suddenly, in a very new way, the conscious and unconscious mind were on public display, re-enforced by sound and silence. The closed audiences of black Cincinnati, I am certain, understood that what they were witnessing was not just their own lives on display, but the parts of their consciousness that white folks could not tamper with. This was their history, as told by their people. And as of yet, white folks did not live there in any meaningful way.

That’s not the blues, that’s not a march, that’s a mix of a kind of cultural subdural hematoma with public displays of language and sound. It is an explosion of cultural self-consciousness and cultural self awareness; and for my money, given the contemporary and imminent, nationwide spread of black awareness in those years, of the intellectual flowering of black ideas and social expectations, along with the stirring of black nationalistic feelings and the explosion of black literature, jazz was just something that had to happen, in a racial space where the lower (in Ralph Ellison’s phrase) and upper (my phrase) frequencies were bound to meet and clash and divide and then come together to make a new art form.

There is, of course, more, there is always more, but I would add, as a list of the kind of unusual characteristics of black (and sometimes white) American cultural practices which were due to converge, the following as contributors to an origin theory of jazz (and probably a bunch of other American styles); pardon me as I quote myself from some prior article expounding on certain cultural elements that, to my way of thinking, are like the satellite elements that produced, at their center, the music I like to call jazz, even if Nicholas Payton thinks otherwise. These were:

The tension between the stiff martial beat of marches and the musically rebellious impulse to accent odd beats (this tension, also out of ragtime, produced, or at least highlighted, the prevalent idea of syncopation which then evolved through composition of early popular tunes, plus the movements and songs of minstrelsy and post-minstrel professional songwriting); the newly emerging industry of professional song writer (late 1800s) as it fed off the musical innovations of minstrelsy and other black and white sources and started to establish a national, standard repertoire of song; the instrumental and rhythm exhibitions of the minstrel stage, employing various black-based methods of percussion (think spoons, juba et al); turn of the century new dances as invented largely by black folks but quickly recognized and adapted and popularized by white folks; the Underground Railroad of hidden black music as performed in a nether, underground, countercultural world of black dance and socializing, and what were, essentially, the secret lives (secret to white folks, that is) of Black America (see Jelly Roll Morton’s Library of Congress interviews to get a strong whiff of this fascinating black counterculture); and black cultural habits as they both altered and adapted to New World ideas of religion and song; and especially African retentions as they played themselves out musically, here and in the Americas, as redistributed by the forced human exports of the Diaspora, and all as documented by people like Lafcadio Hearn and Dale Cockrell (his book); the “Caribbean port-of-call” that was New Orleans (as Dick Spottswood labeled it); and the culturally activist, post-African retentions of New Orleans as publicly exhibited in spaces like Congo Square (where former slaves went to dance and make music in the early years). Add syncopated fiddle tunes as mixed together by black and white fiddlers in the antebellum and post-bellum years and, last but NOT least, black language and black speech as it pervaded, in a cultural-stealth manner, all of the USA, acting upon music, lyrics, colloquial expression, and rhythm (see books with compilations of black lyrics and black word play, as collected by folks like Newman White, Thomas Talley, Dorothy Scarborough, and Howard Odum; there was sound in that speech).

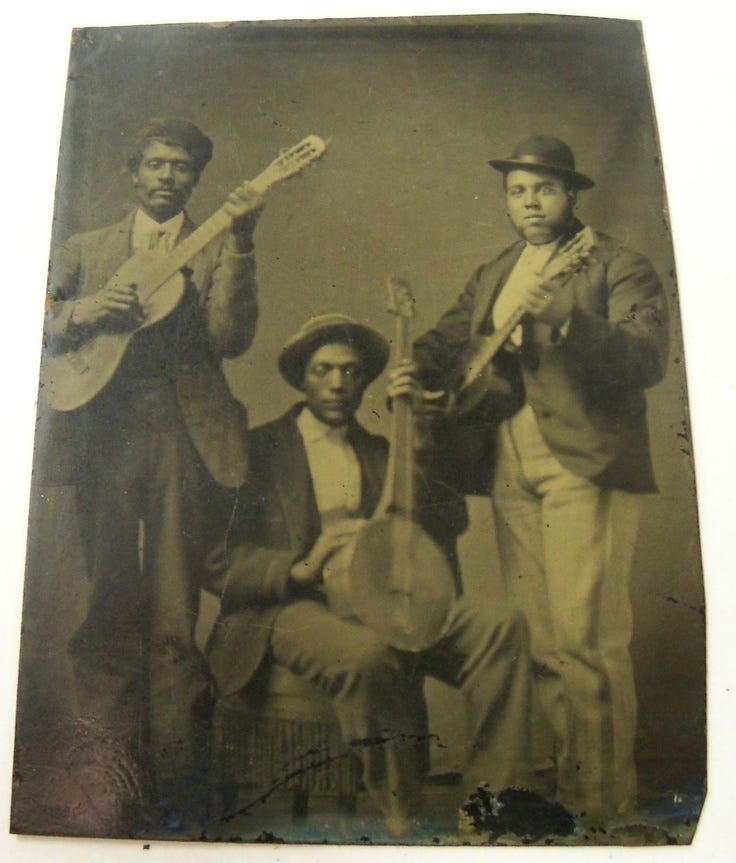

Plus – make witness to the body of black song that comprises what some musicologists called Songsters, black singers whose repertoire often (but not always) skirted the blues and other secular songs; all as sung and recorded by numerous black singers, particularly but not only of the 1920s and 1930s. These songs were a strange and muddled mix of vaudeville/pop tunes, minstrel song, medicine show themes, blackfaced-implying quartet singing, instrumental tunes, and solo vocals, all done by actual black singers who sounded as a mix of street players, religious/gospel performers, jug band (as in homemade) orchestras and vocal contortionists. This wasn’t jazz, but it all made something of a circle around black and white pop and vernacular styles, vocal and instrumental, that would inform jazz with their mix of downhome informality, street sophistication, and concert-level technique. And no matter what the more racially-oriented ideological cultural commentators tell you, they recorded prolifically. Not all black recordings were blues, by a long shot, and someday if I have time and am still cognizant I will do a big-picture series of columns on black music that defies common expectations, just to show that all that is black is not blues – far from it.

In a few days I will post a bunch more musical examples, but just to keep you awake here is the amazing Charleson Rag, recorded as a solo piano piece by Eubie Black in 1921 (called African Rag on the label) and a fascinating recording of the Venezuelan pianist Lionel Belasco; listen to the way that Blake is rhythmically breaking away from ragtime, the emotionally intense striving to define a clear and original musical space; this is jazz, and it is a piece he wrote at least 10 years earlier; but nobody else we hear on record was swinging this much in 1921; then check out the feel of the Belasco record, also solo, with an interesting “latin” feel, very little ragtime, but a gentle way of varying the time: and a very friendly, 2-beat emphasis:

Belasco; listen to the rhythm and check out the piano solo which is very much like “jazz” :

I forgot to note that the Belasco solo, Bajan Girl, is from 1914.

Do you play as well as you write?

You are like the music you describe: a complicated and subtly balanced stew, enlivened by surprising hits of zest and red pepper.